Cook’s New Clothes

Cook’s New Clothes

Royal William Yard, Plymouth

28.09.18 – 21.10.18

Joint Second Prize

Entry in English

On a windy afternoon in late September 2018 a strange parade – part funerary procession, part protest rally – slowly snaked its way around the Devil’s Point peninsula in the Stonehouse district of Plymouth, in the southwest of England. The Second Procession for Tupaia took the form of a cavalcade of customised gilets jaunes, hoisted high overhead on fluorescent poles as ceremonial banners. Loudly proclaiming its presence through a hypnotic Javanese dirge, played on an array of Indonesian wind instruments made from recycled rubbish, the main body of marchers pounded out a relentless rhythm on a makeshift gamelan of plastic bottles and gongs. Occasionally this noisy ‘hi-vis’ throng would come to a grinding halt to bear witness, in solemn silence, to a series of symbolic rituals, performed against the backdrop of Plymouth Sound, looking out to the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

Along with local participants and passers-by, the gathering included artists, writers and musicians from across the Pacific, as well as Europe. The occasion being marked was the death of Tupaia, the Ra’iatean priest and star navigator who accompanied Captain Cook on his first voyage from Tahiti in 1769, in search of the fabled ‘Great Southern Continent’, but who died a year later on 11 November 1770 in Batavia ( now Jakarta ), in the Dutch East Indies ( Indonesia ).

The first version of this processional performance had taken place a week earlier in Greenwich, in southeast London, setting out from the National Maritime Museum and wending its way through the English rain to the banks of the River Thames, where Pacific waka canoes waited to transport the dancing ghost of Cook away to the sea. Adapted in response to the prohibitions of the Royal Museums Greenwich, the central object of institutional anxiety in this closely monitored parade was a dog-skin naval uniform, which had been tailored for the occasion in Australia as a symbolic gift for Tupaia. In order to avoid ‘contamination’ of museum property by the dingo fur, however, the Greenwich authorities had insisted that the cloak should be vacuum-sealed in plastic, bestowing a whole new set of symbolic associations on this gift from the South Pacific. At the same time, the museum’s health and safety guidelines required the performers to wear high-visibility vests, if they were to process beyond the grounds of the institution; a prescriptive stipulation which, in response, was adopted as the central visual motif of the parade.

Gathered under the overall title of Cook’s New Clothes, this multifaceted project also incorporated an installation in the vast, dilapidated Melville Building in the Royal Navy’s former victualling depot in Plymouth’s Royal William Yard, as part of The Atlantic Project, along with related performance lectures, Stubbs’ Dingo and Museopiracy, in implicated sites across the city. Conceived and directed by Austro-Australian artist Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, in collaboration with Maori weaver Keren Ruki, Cook’s New Clothes brought together a cast of participants from across the globe, including choreographer Kirill Burlov, performance artist Nikolaus Gansterer, composer J. Mo’ong Santoso Pribadi and Indigenous Australian scholars Tamara Murdoch and Jessyca Hutchens, among others.

Two hundred and fifty years earlier, on 26 August 1768, Captain Cook’s Endeavour set sail from Plymouth, ostensibly to record the transit of Venus from the vantage point of Tahiti, in the South Pacific, but tasked with a greater secret objective: to seek out and claim the Terra Australis Incognita for King George III. While the 250th anniversary of Cook’s first voyage has received much scholarly attention in recent times, with significant investment in the re-narration of this formative encounter between Pacific and European civilisations, the recognition of Tupaia’s role in this and the commemoration of his death are still largely overlooked. For a quarter of a millennium, the two-way dialogue facilitated through Tupaia’s translation and cultural mediation has consistently been recast as a monologue of Western ‘discovery’. As with the critique of anthropology, it is the mutual ‘coeval’ nature of communicative exchange that has been systematically denied in the ensuing discourse. When Cook encountered Oceanic peoples in the course of his three voyages to the Pacific between 1768 and 1780, he was astonished, not only by their diversity and the extent of their dispersal across the Pacific Ocean – covering one third of the earth’s surface – but even more so by their evident links and commonalities. The similarity of languages, ceremonial spaces, maritime technologies, religious practices and trading networks pointed to a civilisation with a complex history of voyaging and exchange that had existed in parallel with, but virtually unknown to, the West, for thousands of years.

On joining the Endeavour in July 1769, as an ‘ariori’ priest ( a devotee of ‘Oro, the god of fertility and war’, with a long tradition of maritime exploration ), Tupaia was able to list hundreds of named islands, stretching over a vast area of the Central Pacific. Working closely with the Europeans, Tupaia went on to transcribe them onto a map. While Cook, as a leading hydrographer, used instrumental measurements to fix the islands in Cartesian space, gridded by latitude and longitude, Tupaia located them in a relational universe of Polynesian space-time, with star, wind and human ancestors linked to particular people and places in expansive, dynamic kin networks.

One of the most distinctive commonalities of Oceanic culture is the gift economy. It is no coincidence that the seminal early twentieth-century anthropological study The Gift ( 1925 ), by Marcel Mauss, was inspired by instances from the Pacific. Often, ancestral treasures of great mana ( spiritual power ), such as a ceremonial cloak, were deliberately gifted to foreigners with whom the Islanders wished to inaugurate relationships. The significance of the dog-skin uniform in Cook’s New Clothes, along with a cloak made from shredded plastic detritus reclaimed from the Pacific Ocean, is that Cook did not appear to have any such offering within his own collection, as one might have supposed he would. When the Endeavour made landfall at Turanga-nui-a-Kiwa ( Gisborne ) – the first European ship to arrive in Aotearoa ( New Zealand ) – it was Tupaia who led the dialogue, telling the local people that they had sailed from Ra’iatea, in the Society Islands, an ancestral homeland of the Maori. Thus, it was Tupaia, as the leader of an ‘ariol’ expedition, not the European Cook, who was ceremonially welcomed as a tohunga ( expert ), with the gift of a valuable dog-skin cloak.

It seems that Tupaia’s cloak was subsequently inherited, after his death in Batavia, by Joseph Banks, the wealthy young leader of the Royal Society party of botanists and artists on board the Endeavour, who was later famously painted wearing the very same Maori accoutrement by Benjamin West. This powerful artefact now resides in the Pitt Rivers Museum, as part of the University of Oxford’s ethnological collection. It was Banks who had insisted that Tupaia should be welcomed aboard the Endeavour in Tahiti, even though Cook had been reluctant, refusing to support the Ra’iatean or grant him a uniform. In his journal ( 1769 ), Banks wrote of Tupaia, ‘I do not know why I may not keep him as a curiosity, as well as some of my neighbours do lions and tigers at a larger expense.’

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Second Procession for Tupaia, 30 September 2018, processional performance. Courtesy The Atlantic Project. Photo: Dom Moore. 卡蒂嘉·冯·祖内伯格·卡萝尔,《献给图帕亚的第二次游行》,2018年9月30日,行为表演。图片由“大西洋计划”提供。摄影:Dom Moore。

‘How to commemorate Tupaia?’ asks the narrator in the voice-over to Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll’s film Processions for Tupaia ( 2018 ), documenting the events in Greenwich and Plymouth. How to restore subjectivity to this marginalised figure? How to return ghosts to the future? In Johannes Fabian’s book Time and the Other ( 1983 ), the ethnographer analyses a central device in the making of the object of anthropology as ‘temporal distancing’. Situating the Other in a geographically remote and a distant time, such as an ‘archaic past’, is central to how modern Western institutions have created the image of the superiority of the history that they represent. But we know that the Oceanic civilisation Cook encountered was not ‘pre-modern’ or primitive. Indeed, it was highly sophisticated, with a complex history of maritime trade and cultural exchange across more than one third of the earth’s surface. One way of honouring Tupaia’s legacy, therefore, would be to start by calling out the Western fantasy of ‘discovery’, which still persists today, emphasising instead the reciprocity of the dialogue that took place between European and Pacific cultures, facilitated by this remarkable intermediary.

If one were to take the logic of translation further, however, and to understand Tupaia’s map as a re-interpretation of the Atlantic world view from an Oceanic perspective, the question arises: How might this challenge to the ( Mercator ) projection of Western universalism begin to conjure a vision of what decolonisation might look like today? How can Tupaia’s map help to divest Eurocentric modernity of its normative positionality?

At the final station of the Second Procession for Tupaia on Devil’s Point, the gathering watched in silence as Cook walked out into the waters of the Plymouth Sound. The last sighting was of a figure disappearing into the sea, accompanied by the sound of the wind, seagulls and the rhythmic swell of the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

“库克船长的新衣”

库克船长的新衣

威廉皇家庭院,普利茅斯

2018年9月28日-2018年10月21日

二等奖获得者

英文投稿

译 / 梁霄

一场奇怪的游行发生在2018年9月下旬一个刮风的下午:既像是送葬的队列,又像是某种抗议集会。这里是英格兰的西南部,人群缓慢地绕着普利茅斯斯通豪斯区的魔鬼角半岛蛇行挺进。队伍将特制的“黄马甲”塑料衫挂在荧光杆上,高悬于头顶,作为游行的横幅。伴随着一批由可回收垃圾制作的印度尼西亚吹奏乐器发出的声响,在用塑料瓶和锣凑合着敲打出的加美兰节奏中,站在队伍里的人炮制着持续的旋律,通过一首催眠般的爪哇挽歌来大声宣告自己的存在。偶尔,人群中喧闹的“嘿嗞”声会戛然而止,在庄严肃穆的气氛里,队伍将见证一系列以普利茅斯海峡为背景的象征性仪式,同时眺望远处的大西洋。这场为了纪念图帕亚的游行已经表演到第二个版本,除了本地的参与者与路人外,队伍中还包括了来自太平洋彼岸以及欧洲地区的艺术家、作家和音乐家。赖阿特阿岛的祭司图帕亚(Tupaia)是著名的航海家,1769年,图帕亚陪同库克船长从塔希提岛开始了他的第一次航行,企图寻找传说中的“伟大的南方大陆”,但却在一年后的1770年11月11日死于荷属东印度群岛(现印度尼西亚)的巴达维亚(现雅加达)。

游行表演的第一个版本于一周前在伦敦东南部的格林威治得到实现,队伍从国家海事博物馆启程,穿过不列颠的细雨,最终抵达泰晤士河的河岸。在这里,太平洋上的瓦卡独木舟正等待着将舞蹈的库克船长的灵魂带回海里去。这场游行受到了严密监控,并且不得不遵守格林威治皇家博物馆的禁令。游行中最让机构焦虑的核心道具是一件狗皮制作的海军制服,为了这个场合专门从澳大利亚定做,在游行中充当送给图帕亚的象征性礼物。然而,格林威治当局坚持认为,为避免“损坏”博物馆财产,这件由澳洲野狗皮裁制的大衣必须被真空密封在塑料袋里。此举赋予了这件南太平洋的礼物另一套全新的象征意义。与此同时,博物院的健康和安全指南要求,如果要在机构之外进行活动,表演者则必须穿着高能见度的公共安全背心。作为回应,这一规定内容同样被采纳为游行的视觉核心主题。

在“库克船长的新衣”的主题整合下,这一多面性的项目还囊括了一件被安装在梅尔维尔大楼中的装置,这座巨大而破旧的建筑坐落于曾经的英国皇家海军粮仓,普利茅斯威廉皇家庭院。而作为“大西洋计划”(The Atlantic Project)的一部分,项目还伴随着两场在相关地点举行的、与项目主题契合的表演讲座,“斯图布的野狗”(Stubb’s Dingo)与“博物馆剽窃论”(Museopiracy)译注1。“库克船长的新衣”由奥地利裔澳大利亚籍艺术家卡蒂嘉客冯客祖内伯格客卡萝尔(Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll)构思和策划,毛利编织艺术家科伦客瑞基(Keren Ruki)合作呈现,而来自世界各地的艺术家都参与到创作中,其中包括编舞家基里尔客伯洛夫(Kirill Burlov)、行为艺术家尼古劳斯客冈斯特尔(Nikolaus Gansterer)、作曲家莫翁客桑托索客普里巴迪(Mo’ong Santoso Pribadi)、澳大利亚原住民学者塔玛拉客默多克(Tamara Murdoch)和杰西卡客哈钦斯(Jessyca Hutchens)等。

250年前,1768年8月26日,库克船长指挥“奋进号”从普利茅斯起航,表面上是前往南太平洋的天文观测有利位置塔希提岛协助记录金星凌日的现象,但实际却背负着一个更大的秘密任务:为国王乔治三世寻找并占领“未知的南地”(Terra Australis Incognita)。尽管伴随着大量学者针对太平洋文明与欧洲文明接触形成过程的重述,库克首次航行的250周年纪念近期受到了许多关注,但图帕亚在历史中扮演的角色,与对他逝世的纪念在很大程度上仍然遭受了忽视。四分之一个千年以来,通过图帕亚的翻译与文化调节而得以进展的双边对话,一直被解释为西方“发现”的独白。而就人类学批评的角度分析,人们又在后续讨论中系统地否认了相互交流的“同时性”。1768年至1780年,当库克船长在三次前往太平洋的航程中与海洋民族相遇时,他的惊讶不仅仅是由于这些民族的多样性与横跨太平洋的人口分散程度——他们覆盖了地球表面的三分之一——还由于这些民族间更加明显的联系和共性。语言、仪式空间、海事技术、宗教习俗与贸易网络的相似性指向了一个在航海与交流层面具备复杂历史的文明,这个文明与西方文明平行存在了数千年,但实际上后者对此一无所知。

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Second Procession for Tupaia, 30 September 2018, processional performance. Courtesy The Atlantic Project. Photo: Dom Moore. 卡蒂嘉·冯·祖内伯格·卡萝尔,《献给图帕亚的第二次游行》,2018年9月30日,行为表演。图片由“大西洋计划”提供。摄影:Dom Moore。

1769年7月,图帕亚作为一名“埃瑞奥伊祭司”(ariori priest,他们是生育和战争之神奥罗的信徒,发展出了悠久的海洋探险传统)登上了“奋进号”,他能够列出数百个岛屿的名字,这些岛屿覆盖了太平洋中部的广大地区。图帕亚随后与欧洲人密切合作,将这些岛屿记录在地图上。库克是一位杰出的水文学者,他利用仪器测量将这些岛屿的位置固定在由经度和纬度搭建的笛卡尔空间中;相反,图帕亚通过一个相对的波利尼西亚时空宇宙来寻找这些岛屿的坐标:在一个广阔而动态的族源与亲属网络中,恒星、风与人类的祖先总是与特定的人群和地点相连。海洋文化最显著的共性之一是“礼物经济”。20世纪早期开创性的人类学研究——马塞尔客莫斯(Marcel Mauss)的《礼物》(The Gift,1925)——受到来自太平洋的实例启发,这并不是什么巧合。和强大的“马那”(mana,精神力量)连通的祖传珍宝,比如一件用在仪式上的斗篷,通常会被岛民有意赠送给部落外面的人,他们希望借此建立关系。在“库克船长的新衣”中,狗皮海军制服与另一件由从太平洋回收的塑料碎片制成的斗篷因此具有重要的意义:库克自己的收藏中似乎没有任何一件这样的礼物,但人们可能认为他有。当“奋进号”作为抵达奥特亚罗瓦(现新西兰)的第一艘欧洲舰船,在“Turanga-nuia-Kiwi”(现吉斯伯恩,新西兰北岛东岸港市)靠岸时,是图帕亚主持了船员与当地土著人的对话。他告诉他们,船从“社会群岛”的赖阿特阿来,而“社会群岛”则是毛利族祖先的故乡。所以,是图帕亚作为“埃瑞奥伊海洋探险”的领队祭司受到当地人隆重的欢迎,而不是船长库克。图帕亚被视为“tohunga”(专家),并且获得了一件珍贵的狗皮斗篷。

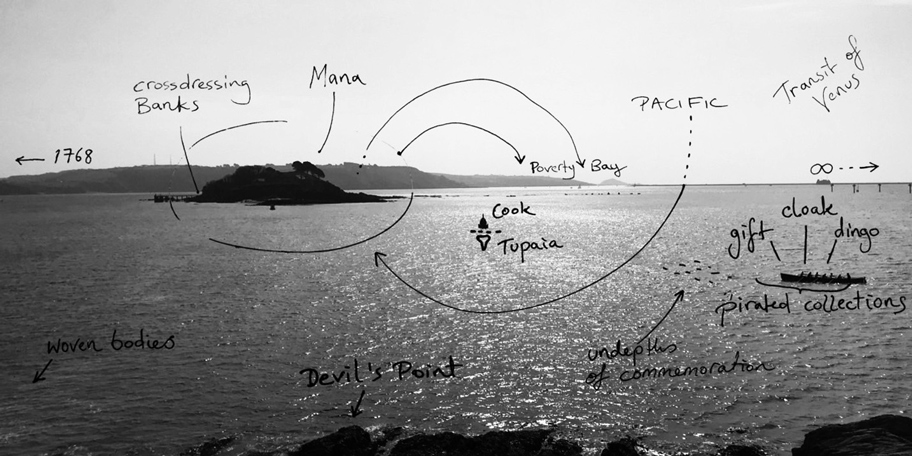

Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, Cook’s New Clothes, 2018, drawing on photograph, 14.8 × 21 cm. Courtesy The Atlantic Project. Photo: the artist.卡蒂嘉·冯·祖内伯格·卡萝尔,《库克船长的新衣》,2018年,摄影手绘,14.8 × 21 cm。图片由“大西洋计划”提供。摄影:艺术家。

当图帕亚在巴达维亚死后,约瑟夫客班克斯(Joseph Banks)继承了这件礼物。由植物学家和艺术家组成的英国皇家学会的部分成员当时也在“奋进号”上,约瑟夫客班克斯是他们年轻富有的领袖。在著名画家本杰明客韦斯特(Benjamin West)后来为班克斯绘制的一张肖像中,他正穿着这件毛利人的斗篷。这件具有魔力的斗篷现被保存在牛津大学皮特河博物馆,属于牛津大学民族学收藏的一部分。恰恰是班克斯在塔希提岛时坚持认为,应该欢迎图帕亚登上“奋进号”,尽管船长库克并不情愿,他既不想支持这个赖阿特阿人,也不想给他一件制服。在日记(1769年)中,班克斯提到了图帕亚:“我不知道为什么我不能像我的一些邻居,像他们花大价钱饲养狮子和老虎那样,把他当作珍奇之物。”“该如何纪念图帕亚?”卡萝尔的影像作品《为图帕亚游行》(Processions for Tupaia,2018)记录了发生在格林威治与普利茅斯的两次活动,其中的画外旁白如此问道。该如何恢复这个边缘形象的主体性?“该如何将鬼魂送回未来?”人类学家乔纳斯客费边(Johannes Fabian)通过著作《时间与他者》(Time and the Other,1983)分析了人类学对象形成的一个中心机制,即“时间距离”。将“他者”置于某一偏远的地理位置和某一遥远的时间,例如“远古的过去”,是现代西方制度如何创造其所代表的历史优越性形象的关键。但据我们所知,库克船长遭遇的海洋文明并非是“前现代”或原始的。事实上,这种文明高度复杂,在跨越了地球表面三分之一的地理区域内创造了海洋贸易与文化交流的深刻历史。因此,纪念图帕亚传奇的一种方式,将是首先唤醒西方直至今天也依然存在的关于“发现”的幻想,取而代之需要强调的则是欧洲与太平洋文化之间对话的“相互性”,这样的对话正是由图帕亚这位了不起的中间人所促成的。然而,如果我们进一步采取转译的逻辑,将图帕亚的地图理解为海洋视角下对于西方世界的重新阐释,问题便会层出不穷:这种对西方普世主义的墨卡托译注2投影所发起的挑战,将如何能够召唤出如今关于非殖民化的想象?图帕亚的地图又该怎么帮助以欧洲为中心的现代化剥除自身规范性的关系结构?为了纪念图帕亚的第二次游行结束在魔鬼角,人群聚集起来,在肃穆中注视着“库克船长”走入普利茅斯湾的海水中。他的背景最终消失在大海里,伴随着风声、海鸥的叫声以及远处大西洋层层叠叠的波涛声。