The Secret Message in the Image

Julien Bismuth: Steganograms

The Box, Los Angeles

19.09.15 – 31.10.15

Think of the ways one might send a message securely: mail a letter, have a conversation in a busy restaurant, make a call on a random payphone – if you can find one. Then again, maybe you have no reason to send a message you have no reason to hide. Of course. In Steganograms, at The Box in Los Angeles, the artist Julien Bismuth, through a series of new photographs, texts, video, collage, a sound piece, conceptual projects, and a performance that happened before the show opened, seemingly has nothing to hide. But this show successfully explores the fascinating ways in which hiding information can be intriguing, and interpretation subverted.

The main bulk of the works in Steganograms is encrypted photographs. Bismuth came up with this neologism based on the practice of digital steganography, which is a form of cryptography in which a text, or image, is embedded within another image through coding. Bismuth made photographs with a 35 mm camera, digitised the images, wrote texts, and then combined them together with a programme designed by his cousin, Vincent. Each digital image has a code of bits representing the colours of the image, and if you alter some bits for other bits – say, a legible text – at varying levels, the image is more or less abstracted with visible or imperceptible digital noise.

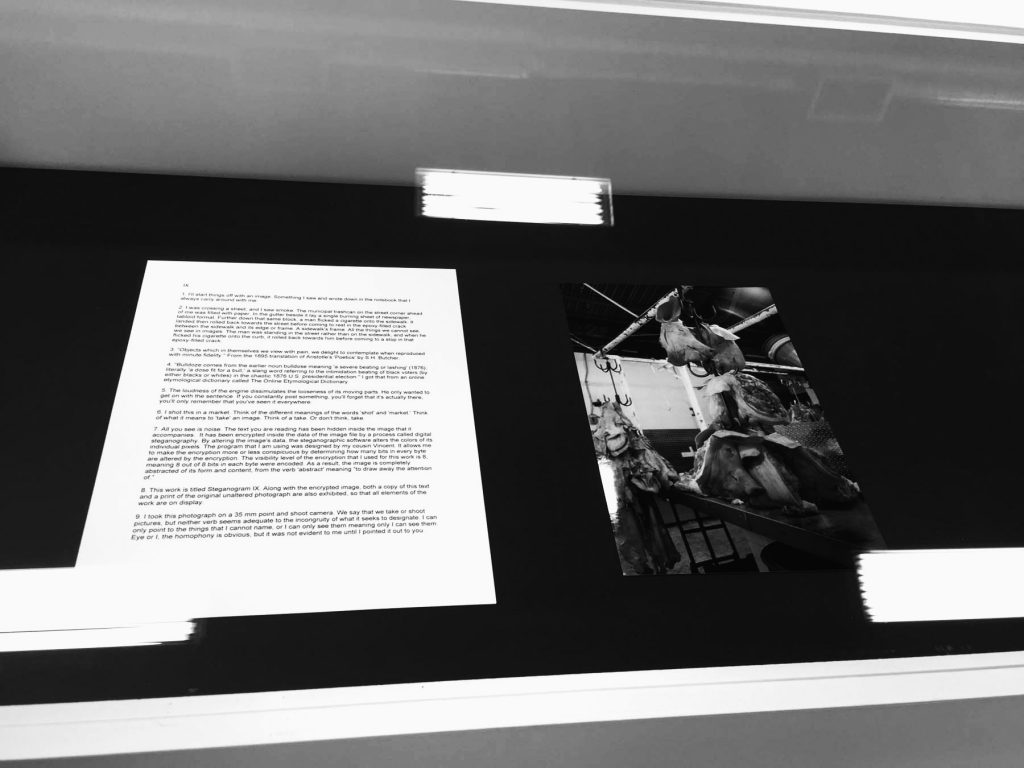

Bismuth exhibits his steganograms framed on the wall, and then shows the original image along with the text that has been embedded in vitrines in the centre of the gallery. As you are looking down into the vitrines, the corresponding steganogram hangs across the way on the facing wall, with varying degrees of grained and pixilated abstraction. This makes the encryption process very transparent – far from the usual sort of steganography that has been used for everything, from film studios sending out film screeners that they want to be able to trace, to Al Qaeda transmitting messages through videos. A well hidden message, in steganography, will show nothing out of the ordinary if you don’t know the message is there.

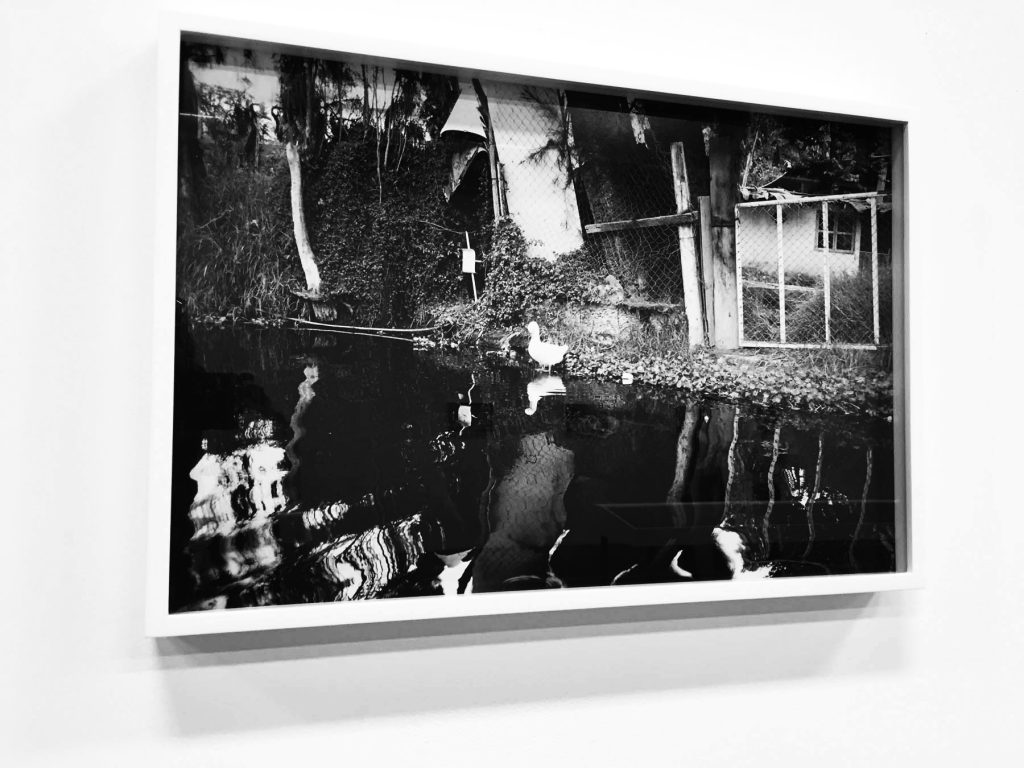

The texts on display read like automatic writing, the coded language of the unconscious. Bismuth writes in the text to Steganogram II that he is composing as if he were writing an email, ‘so as to feel as if I were addressing someone or something’. These are haphazard notes, with memories, repeated explanations of the steganography process, and snippets of dreams. Rarely do they address what the photographs are of: a white duck on the bank of a river, a heap of compost, pig carcasses in a slaughterhouse, or an insect in mid-flight. As Bismuth puts it in the press release, each image has been ‘coloured’ by the text, and this is what fascinates him. Seeing all of Bismuth’s ingredients, however, and the intentionality of grainy abstraction, provokes one to seek deeper meanings and codings. One might ask: Is there something else embedded in these images, along with the text? We may never know for sure.

Studying and puzzling over Bismuth’s creations, we begin to notice the recurrence of certain details that demonstrate Bismuth’s feelings about abstraction and comprehension. The performance that happened before the show opened had Bismuth in front of an audience, writing on a piece of graph paper that was projected onto a screen, for all to see. The video of this is displayed on a piece of frosted glass perpendicularly mounted to the wall, with the actual written-on graph paper posted to the back. He writes on the graph paper about losing his bearings in Los Angeles: ‘That is what I think abstraction is, when we speak of abstraction in an image. It is a loss of one’s bearings.’ And in the text for Steganogram III, he writes: ‘I only really start to see an image once I forget what it’s about.’ And in Steganogram IX: ‘All the things we cannot see, we see in images.’ And, finally, in Steganogram X, in writing about his cousin’s software program that he uses to encode the image, and on computers in general: ‘The blindness of a processor is the purest, as in most unsuspecting, form of blindness.’ The works in this exhibition imply that to see is not to know; it’s only when we start asking questions, and forgetting sight, that we begin to experience what is there. But what comes after this ‘beginning’ can continue as a series of beginnings, with no end.

On the whole, there is no whole here. The show is a series of fragments that are difficult to make sense of together. Along with the steganogram sets and the video/graph paper, Bismuth includes another video on a flat-screen display of a hand waving around over a scan of two pages of the mathematician Kurt Gödel’s philosophical notebooks written in a nineteenth-century form of German shorthand called Gabelsberger after its inventor. The voices in the video are translating the text, which relates to time. The readers lose their place and have to begin again. ‘Time is thus both the topic and the protagonist of the video’ writes Bismuth in the press release. The show also includes Bismuth’s Titular Works – works that are based on titles but have little overt essence other than actions, words or punctuation. For example, two holes cut in the gallery wall, a giant colon, are titled ( 2015 ). There are also vast expanses of wall that Bismuth calls 555 by 1280 cm ( 2015 ) and 35 by 199 inches ( 2015 ) which are just that – units of measurement between other works. In the press release, Bismuth remarks that he keeps ‘wanting to fill these vacancies with something else: a title, a reference, an allusion. But I think I’ll try to leave them vacant for as long as I can.’ In my correspondence with Bismuth he did mention an allusion for the larger of these works: the exact dimensions of Paolo Veronese’s Feast in the House of Levi ( 1573 ), a work originally titled Christ in the House of Levi, but the painting was too filled with ‘sinners’, and so Veronese changed – or perhaps coded – the name.

What’s essential to viewing this show is having an open mind – one might want to definitely avoid looking for answers in a review like this or, to any satisfaction, the press release. On first glance, the surfaces here are not exactly aesthetic, the photographs on the wall not much more than well-presented snapshots. There are more ideas than attractions ( although I must say, the sound piece Helena Valero ( 2015 ) is quite beautiful in its simplicity – a pair of headphones hanging from the ceiling, from which a woman’s voice sings unintelligible, ghostly songs, which the press release advises one to research further, using her name ). Each piece in this exhibition comes with a story that raises more questions than it answers, and this why the exhibition has merit. There is something innervating and stimulating here that tells me that knowing it all may just turn out to be a dead end. If we can keep searching for the codes, the ciphers and the source, life will continue feeling very full. One day we may realise that our greatest intelligence is that there is no explanation, and no algorithm, to solve it all.

图像中的秘密讯息

《朱利恩比斯姆士:密码》

洛杉矶,盒子画廊

2015年9月19日 – 2015年10月31日

试想一下一个人会通过哪些安全的方式传递信息:邮寄信件、在一间喧哗的餐厅内进行对谈,或在一部随机选取的投币电话上拨打电话金如果你能找到一种的话。再说,你也可能没有理由去传递一个你没有理由会隐藏的信息。事实当然如此。在洛杉矶盒子画廊的展览“密码”中,透过一系列新近完成的摄影作品、文本、录像、拼贴画作、声音作品、概念性项目以及在展览开幕前的一场表演,艺术家朱利恩比斯姆士( Julien Bismuth )似乎别无隐藏。然而,这个展览成功地探索了隐藏信息的迷人之处,以及如何通过解码来颠覆信息的原意。

Julien Bismuth, Steganogram VII, 2015. Inkjet print, 15 x 221/2 in. 朱利恩·比斯姆士,《密码系列之七》,2015年,喷墨打印,15 x 221/2 英寸.

展览“密码”中的主要板块是“加密照片”( Encrypted Photographs )。比斯姆士通过使用数字图像隐码术( Digital Steganography )提出了上述新名词。所谓“数字图像隐码术”是一种通过编码将其他的图像嵌入当前文本或图像的加密形式。比斯姆士用一部35mm相机拍照,将照片数字化,写上文字,然后用一种由他的表兄弟Vincent设计的电脑程序将它们组合起来。每一款数码图均有一个数位代码来表示该图的颜色。假如你将其中一些数位在不同的层面上用另一些数位金比如一段字迹清晰的文字金来替代的话,该图将或多或少被可见的或觉察不到的数码噪点所虚化。

比斯姆士将他的密码作品装裱起来挂到画廊的墙上,并将原图与文本同期展陈于展场正中心的橱窗内。当你俯视橱窗时,与原图和文本相应的、被不同程度颗粒化且像素化的密码图像则悬挂于对面墙上。这令加密过程变得远比一般的图像隐码术透明得多。普通的图像隐码术被广泛运用,从制片室向电影筛选者送出他们想要追踪的影像作品,到基地组织通过录像发送口讯。在图像隐码术中,如果你不知道信息原本就在那里的话,一则隐藏得很好的信息将与常态无异。

Julien Bismuth, original image of Steganogram IX, 2015. C-print, 10 x 65/8 in, with inkjet print of text to be encrypted. 朱利恩·比斯姆士的作品《密码系列之九》之原图( 彩色负片冲印,2015年,10 x 65/8 英寸 ), 附上用来加密的文本打印稿.

展览中的文本读上去像是自动书写出来的、被编程的无意识语言。比斯姆士在他的作品《密码系列之二》的介绍中写到,他仿佛是写电邮一般创作出这些文字,“以便让人感到似乎是我在称呼某人或提及某件事情”。这些文字是偶然的记录,带着回忆,是对图像隐码过程的重复解释,也是有关梦境的片段。文本中很少提到相应的照片是关于什么的,像是河岸边上的一只白色鸭子,一堆堆肥,一间屠宰场内的死猪尸体,抑或是一只飞行中的虫子。正如比斯姆士在新闻稿里所说的,每一个图像均已被文字所“上色”,而这正是令他着迷之处。然而,在看过比斯姆士所有展品以及有意为之的颗粒感抽象化效果之后,让人不由地想探寻其中蕴藏的更深的含义和编码。你可能会问,在这些图像及相应的文字里面,是否嵌入了其他什么东西?当然,我们可能永远不会知道。

Installation of Julien Bismuth, Steganograms, The Box, Los Angeles. 朱利恩·比斯姆士《密码》,装置,洛杉矶盒子画廊.

当我研究并困惑于比斯姆士的创作时,可以不断看到某些展现比斯姆士对抽象概念及领悟力的感受的细节。在展览开幕前的表演把比斯姆士带到观众面前,当时的他在一张图纸上进行写作,写出的文字被投影到一个屏幕上,让在场所有人都能看到。整个过程的现场录像则被显示于一块垂直悬挂在墙上的磨砂玻璃上,玻璃的背后贴着那张写着字的图纸实物。在这张图纸上,比斯姆士写下了他在洛杉矶迷失方向的经历:“当我们谈及一幅图像的抽象概念,那就是我所认为的抽象概念所在,即让人迷失方向的感觉。” 而在其作品《密码系列之三》的文字描述中,他写道:“当我忘记一幅图像是关于什么的时候,我才真正开始看到这幅图像。”在其作品《密码系列之四》中写道:“凡是我们无法看到的东西,我们都可以在图像中看到。”最后,在《密码系列之十》中,当比斯姆士提及自己曾经如何将其表兄弟的软件程序编码到图像及关于广泛意义上的电脑时,他写道:“( 电脑 )处理器的愚昧是最纯粹的,一种最令人信服的愚昧形式。”本次展览中的众多展品均暗示了以下的信息:看见并不等于是知道;只有当我们开始提出疑问,并忘记所见,我们才会开始体验到事物的究竟。但这样的开始可以继续衍生出一系列的开始,无穷无尽。

总而言之,这里并没有一个整体。这场展览由一系列片段体组成,而这些片断在拼接之后却令人难以理解。除了密码装置以及录像/图纸之外,比斯姆士在展览中还加入了另一部用平板屏幕展陈的录像作品,画面中是一只手指向两张有关数学家库尔特哥德尔( Kurt Gödel )所写的哲学笔记的扫描图,该笔记是用一种根据其发明者而命名的十九世纪德文速记形式金加贝尔斯贝格速记法( Gabelsberger )写成的。录像中的声音正在翻译这份笔记,内容是有关时间的。读者若错过相关内容的话,就得重头再听。“这样一来,时间不仅是这部录像的标题,同时也是其主角。”比斯姆士在新闻稿中如此写道。展览还囊括了比斯姆士的《有名无实的作品系列》金这些作品以标题为基础,但除了动作、文字或发音之外几乎没有其他明显的元素。举个例子,在画廊墙上切割出两个洞,从而组合成一个巨型的冒号标点,题为《:》 ( 2015年 )。此外,比斯姆士还将展场中的几块宽大的墙面命名为《555×1280厘米》及《35×199英尺》,仅仅作为与其他展品之间的度量单位。在新闻稿中,比斯姆士提到他一直“希望用其他的什么东西填补这些空缺:比如一个标题、一个注释,或一个典故。但我认为我还是会将它们的空缺状态保持一段尽可能长的时间。”在我与比斯姆士的通信往来中,他的确提到一个典故:这些墙面作品中较大的那个作品的尺寸其实与保罗委罗内塞( Paolo Veronese )于1573年创作的《利未家的盛宴》的实际尺寸相同。这幅作品原本题为《利未家的基督》,然而由于画中充斥着太多“罪人”,因此艺术家将其名称更改( 抑或可能重新编码 )了。

欣赏本次展览的重点是保持一种开放的心态金你或许的确想要避免在像这样的一篇评论或新闻稿中寻求任何令人满意的答案。乍一看,这里的展品表面上确实并没什么美感,墙上的照片充其量也只能当作是一些拍得不错的快照。相对吸引力而言,这些展品更以理念取胜( 尽管我必须说,展品中那件名为《Helena Valero》( 2015年 )的声音作品十分具有简约之美金一对耳机从天花板上垂挂下来,里面传来一个女人用朦胧的嗓音唱着难以明了的歌曲,新闻稿中则建议观众用她的名字做进一步的研究 )。本次展览中的每件展品都向观众述说着一个故事,故事带来更多的是疑问而非答案,而这正是展览的价值所在。展品中有某些东西令人感到刺激,告诉我如果知道全部的话只会让人陷进死胡同。如果我们能持续寻找代码、密码及源头,人生将一直充实无比。有一天我们可能会领悟到的最大智慧就是并没有解释,亦没有演算法则来解决生命中的所有问题。